Two of my former Danish flatmates in Aarhus wrote to me last night about the resurgent cartoon controversy. One wrote: “I don’t really think that’s the correct solution in this situation, and we can’t continue to enrage them like this.” The other updated me on how the domestic media were handling the affair, along with his interpretations of the political landscape:

Yes I just read it on the news paper Politiken’s homepage. Though making a fuss about it being printed in a newspaper seems strange since they are shown on TV each time they mention the cartoonist.

The three news papers are Berlingske Tidende, Politiken and Jyllandsposten (JP).

It is quite remarkable that Politiken prints them since its chief editor, Thøger Seidenfaden, led the criticism against JP back then. Also Berlingske Tidende have not printed them before.

It could seem Seidenfaden is afraid to end up looking like a bad guy defending the religious fanatics (in the Danish media at least) as he did the last time.

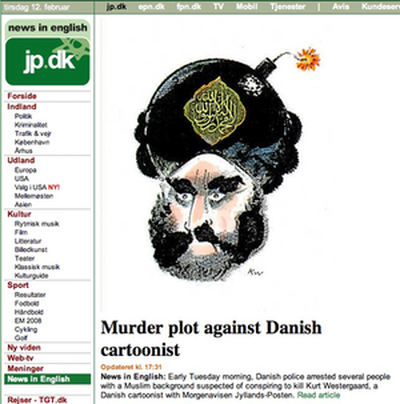

http://jp.dk/indland/article1263415.ece

http://politiken.dk/indland/article470475.ece

http://www.berlingske.dk/article/20080212/ledere/80212059/

And yeah the place the police raided was just where the 15 goes by.

***

The “15” to which he refers is the bus route we all took to and from central Aarhus from the lovely Skjoldhøj. It passes through what is often called the largest ghetto in Denmark, Gellerupparken, for its sizable immigrant population. After visiting the local DR TV and radio stations in Aarhus, I thought the opinions expressed by media personnel about Gellerupparken bordered on the paranoid.

The personal stories I had heard from ethnic Danes about interaction with minorities in Aarhus did not sound good, either. One flatmate, who looks as Viking and Nordic as possible with his pale blond hair, blue eyes, and almost bloodless skin, described a walk he took through a grassy area in Gellerupparken. He had just gone grocery shopping and decided to take a shortcut home. It was the middle of the afternoon, bright and sunny. As he walked through the park, some elementary school kids of minority descent started shouting at him “f*ckin’ Dansker”—”f*ckin’ Dane.” In another incident, he was sitting at the back of the bus when a group of boisterous, minority teens boarded the bus (you board from the back in Denmark). They exhibited loud, intimidating male behavior and moved to the front of the bus, where a fellow classmate of his sat. He described this classmate as “about as harmless and dorky as you can get.” Right before the teens exited the bus, one turned to the unassuming kid and spat in his face. They laughed and ran out. My flatmate, outraged, sat there stunned. Then, he looked behind him and noticed a big wad of spit oozing down the window behind his head. They had missed.

I noticed a bit of the tension in Denmark myself, as a minority “not of contentious origin”—there aren’t many East Asians, and the ones there keep to their own communities. It is also disarming, I imagine, for a foreigner to hear me speak perfectly fluent English. So I found my situation different from those of my other international classmates. Almost all Danes I encountered were super friendly and helpful. I remember my first extensive contact with a Dane was with the bus driver who drove me from the airport to the city. He went out of his way to figure out my rendezvous site with my mentor, and took pains to drop me off at another location not really on the bus route.

The “contentious minorities” in Denmark mostly left me alone. One time I was walking to the #15 bus when a car slowed down and stopped. A dark-skinned man asked me which direction I was heading. Puzzled, I told him I was going to football practice. “Oh,” he said, “I am going to the opposite side of town, otherwise I would drop you off.” It was random and nice, and I don’t think he had any ulterior motives except to help out.

Most forced social interaction happens on the bus. Public transport is sometimes the only way in which people experience the “other,” which is why I like New York City so much, as opposed to Los Angeles. You’re forced to encounter all kinds of people and behavior in daily life. And since you’re practically living on top of your neighbor, squeezed up against some guy’s bum on the subway, or dining with someone’s elbow in your soup, most people eventually form many relationships they would not normally have elsewhere. Los Angeles, its polar opposite, facilitates strong cliques based on location and familiarity. People stay in their cars and communities and ethnic leanings, creating a relative—but separate—peace in the California sunshine.

Aarhus sits in a precarious spot between the extremes of New York and Los Angeles. There’s enough interaction to increase prejudice, but not enough to forge relationships and understanding. Another time I sat on the bus with a classmate when a loud minority male got on the bus sporting a backwards baseball cap (a universal sign of “dunce”). He sat behind my classmate and proceeded to hit the back of her seat obnoxiously, completely aware of his actions. My soft-spoken African classmate endured the thumps. After several minutes of repetitive whacks, I turned deliberately and made eye contact. He carried on, in what I am sure he considered to be a defiant and cool attitude. Right at the moment I was about to say something loud and attention-gaining, he stopped. A group of school kids boarded the bus; they formed an animated mass of blond heads and cherubic cheeks rouged by the winter winds—except for one. A cute dark-haired, dark-skinned boy romped around with the other kids, laughing and talking in a scene typical of my multi-ethnic hometown, Cerritos, California. Mr. Knucklehead noticed this kid, too. And as he stood up to exit the bus—in sharp contrast to the disenfranchised, boorish demeanor with which he greeted the rest of the world—he tenderly tousled the boy’s hair and went through a “got-your-nose” routine with him. The boy, puzzled and a bit disturbed, immediately went back to his friends.

I noticed The New York Times removed its characterization of Aarhus as a “quiet university town” today in the cartoon arrests story from last night. An experienced editor, no doubt, knew that such a simplistic characterization is almost never on the mark.

Robin