The Dutch wires are reporting at this hour that in the wake of today’s arrests in Aarhus, Denmark for a plot to assassinate one of the cartoonists involved in the 2005 Prophet Mohammed caricature controversy, three of the largest Danish newspapers have decided to republish the cartoons.

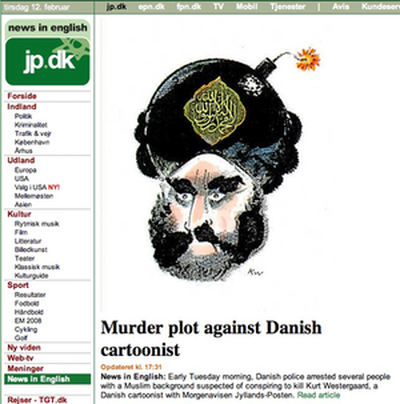

Jyllands-Posten, the original perpetrator, already has a cartoon displayed prominently on their English Web site.

After examining media in Denmark last fall, many of our classmates have grown weary of the whole Danish cartoons affair. In fact, two of the required readings from last week focused exclusively on the media’s role in the brouhaha and how minorities are portrayed in Denmark. One text published in 2000 by Mustafa Hussain analyzed Islam and minorities in Denmark, asserting that an “interdiscursivity of powerful societal institutions” promotes a negative public opinion, creating political intolerance (97-98).

On a comparative scale with other European nations, Denmark stands out. Hussain offers supporting evidence:

- Only 17 percent of Danes reported they were absolutely non-racist, according to a 1997 European Commission survey on racism, qualifying as the lowest percentage of self-defined non-racists in the EU. For comparison, the average EU self-defined non-racist was 34 percent; fellow Scandinavian country (and place where all is sweetness and light) Sweden was even higher at 42 percent.

- 83 percent of replies in Denmark scored as having low to very high racist attitudes in the same study. Again, for comparison: Austria and Germany, both associated with neo-Nazi movements, both hovered around 70 percent.

- Despite this, Denmark has one of the smallest percentages of immigration in the EU from countries outside the EU, Eastern Europe, and North America.

- 37 percent of Danes would not want to have a Muslim for a neighbor and 64 percent would not want a close family member to marry a Muslim. These figures drop considerably to 18 percent and 36 percent, respectively, when “Muslim” is replaced by “a person of another race,” according to a 1995 national survey by two political scientists from Aarhus University.

- 85 percent of ethnic Danes had no social interaction with minority individuals or groups, as cited in the previous study.

These statistics seem damning, but it’s much more complicated than simply concluding that Danes are simply more racist. Hussain analyzes how the media influence public opinion through the use of repetitive headlines, negative minority topics (like crime, immigration, and other problems), and creating an us-versus-them framework for stories. Public service media were worse offenders than commercial media in this regard.

Hussain uses John Zaller’s theory on the origin of and formation of mass opinion to support his idea on media influence. In a nutshell, Zaller’s theory says that people’s opinions depend on the “ideas and thoughts activated immediate” rather than a thorough evaluation on the subject in question (Ibid. 101). So whatever the dominant information flow is at the time—as perpetuated by the media—will also dominate public opinion. Given that most Danes have little to no experiential knowledge of minorities, this phenomenon is perhaps even stronger.

Another text, a book written after the cartoon controversy in 2007, analyzed the media’s handling of the controversy in 14 different countries. The authors claim that an editorial in The Economist sparked the initial idea for the project: to understand how “freedom of speech was defined, defended, and criticized,” under international scrutiny, both in and by the press (Kunelius and Eide 9). One of the researchers, in an essay called “The Right to Communicate,” took the moderate stance, weighing individual expression against duties towards society. “[T]he right to be understood,” he writes, should imply that others have a duty to try and understand the “other.” This requires society to “distance itself from egocentric acts of communication” (Ibid. 19).

Now that the controversy looms large once again, our project to interview minority media outlets here in the Netherlands might take a more interesting twist.

Stay tuned…

Robin

References

Hussain, Mustafa (2000). Islam, Media and Minorities in Denmark.

Current Sociology,48(4), 95-116.

Kunelius, Risto, & Eide, Elisabeth (2007). The Mohammed cartoons, journalism, free speech and globalization. In Risto Kunelius, Elisabeth Eide, Oliver Hahn & Roland Schroeder (Eds.), Reading the Mohammed cartoons controversy: an international analysis of press discourses on free speech and political spin (pp. 9-23). Bochum/Freiburg: ProjektVerlag. Available online at

http://ncom.nordicom.gu.se/ncom/research/the_mohammed_cartoons_journalism_free_speech_and_globalization(19166)/

the time to read or visit the content or sites we have linked to below the…

here are some links to sites that we link to because we think they are worth visiting…

Magnificent beat ! I wish to apprentice while you amend your web site, how can i subscribe

for a weblog website? The account helped me a appropriate deal.

I were tiny bit familiar of this your broadcast provided brilliant clear

concept